RSS is Inheriting Mahatma Gandhi’s Legacy

In the wake of over 150 years since the birth of Mahatma Gandhi, the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) is emerging as the true heir to Gandhi’s legacy. Gandhi, a devout Hindu, advocated for principles such as Hindu Dharma, cow protection, Swadeshi, and the elimination of untouchability, which the RSS claims to have continued.

In 1934, Gandhi visited an RSS training camp in Maharashtra and was impressed by the organization’s practice of young men and boys from all castes living and eating together without being restricted by caste differences. Even after Independence, in a speech to RSS workers in 1947, Gandhi praised the discipline, absence of untouchability, and rigorous simplicity within the organization.

Interestingly, Dr. B.R. Ambedkar, the architect of the Indian Constitution, also visited an RSS training camp in 1939. Ambedkar, known for his efforts against untouchability, was surprised to find Swayamsevaks moving about with equality and brotherhood, regardless of caste.

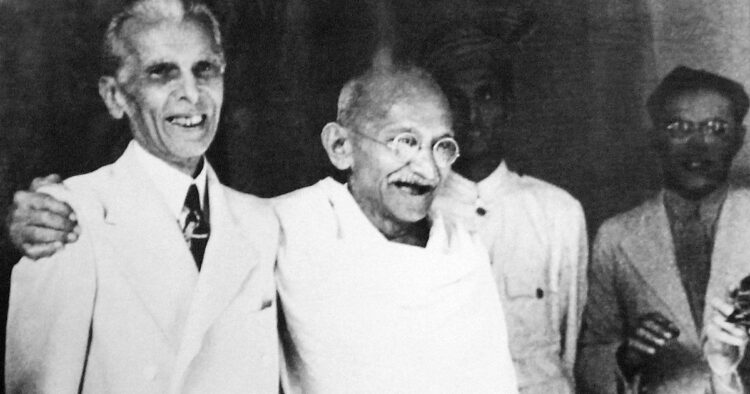

A notable comparison is drawn between Gandhi and Pandit Deendayal Upadhyaya, a senior RSS ideologue and a founder of the Bharatiya Jana Sangh. Both Gandhi and Upadhyaya were charismatic organizers with a grounded approach to intellectualism. They shied away from direct political power, emphasizing selfless service and the rejection of Western models of development.

Gandhi’s focus on ‘Swaraj’ and ‘Swadeshi’ aligns with Upadhyaya’s philosophy of ‘Integral Humanism.’ Both leaders were suspicious of political power, emphasizing the corrupting influence it had on public figures. Gandhi’s suggestion to abstain from power politics was rejected by Congress colleagues, while Upadhyaya, as a political party leader, may have resonated with Gandhi’s views on politics.

The common thread between Gandhi and Upadhyaya lies in their belief that the quality of individuals in society determines the nature of the state. The RSS claims to have tirelessly undertaken the task of preparing such individuals for the past 93 years, positioning itself as the sole organization carrying forward Mahatma Gandhi’s legacy. In this light, it asserts itself as the true heir to the ideals and principles espoused by Gandhi, aligning with the vision of a selfless, service-oriented, and nationalist society.

RSS and Mahatma Gandhi’s Assassination: Debunking Myths with Facts

Accusations linking the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) to Mahatma Gandhi’s assassination have been a persistent narrative, notably voiced by figures like Rahul Gandhi. However, a closer look at the facts tells a different story.

On January 30, 1948, around half an hour after Gandhi’s assassination, the First Information Report (FIR) was filed at the Tughlak Road police station. Nand Lal Mehta, an eyewitness, provided a statement describing the events leading to Gandhi’s death. Interestingly, the RSS chief, MS Golwalkar, was attending an RSS meeting in Chennai at the time.

Golwalkar’s immediate response to the tragic news demonstrated his genuine grief. He sent telegrams of condolences to prominent leaders and canceled his countrywide tour, flying back to the RSS headquarters in Nagpur. In an unprecedented move, all RSS Shakhas were closed for 13 days to mourn Gandhi’s demise, breaking the organization’s tradition of holding daily sessions.

Golwalkar’s letter to Prime Minister Nehru expressed sorrow and highlighted the responsibility of steering the nation forward during troubled times. Despite these expressions of grief and solidarity, the government banned the RSS on February 4, 1948, and arrested Golwalkar, invoking the Bengal State Prisoners Act. This was a controversial move, considering Nehru had criticized the act as a ‘black law’ before independence.

Released after six months, Golwalkar faced another arrest later. A satyagraha by RSS volunteers ensued, with over 77,000 Swayamsevaks courting arrest. Yet, the government failed to find any evidence against the RSS.

A month after the assassination, Sardar Patel wrote to Nehru, asserting that the main accused had given detailed statements, and it was clear the RSS was not involved. Another letter from Patel to Golwalkar expressed his happiness at the lifting of the RSS ban on July 12, 1949.

Despite these clarifications, allegations persisted. In 1966, Prime Minister Indira Gandhi’s government established a judicial commission, led by Justice JL Kapur, to thoroughly probe the assassination. The commission’s findings, published in 1969, debunked the notion that the accused were RSS members or that the organization had a role in the murder.

One crucial witness before the Kapur Commission was RN Banerjee, the home secretary to the government of India at the time of the assassination. The commission’s report emphasized that there was no evidence of the RSS engaging in violent activities against Gandhi or top Congress leaders.

In conclusion, the historical record, including witness testimonies and judicial investigations, refutes the allegations linking the RSS to Mahatma Gandhi’s assassination. The organization’s immediate response, expressions of grief, and the subsequent legal proceedings all support the narrative that the RSS was not involved in this tragic event.

Comments