KEY POINTS

- Mukherjee saved Hindu-majority Bengal from becoming part of Pakistan.

- Without him, Bengali Hindus might have faced mass persecution.

- Mukherjee offered a nationalist, self-reliant vision against Nehru's appeasement path.

After India adopted the Muslim League’s ‘Two-Nation Theory’, the partition became inevitable. Jinnah remained firm on his demand. But what options did Bengalis have in that scenario? What might have happened if Syama Prasad Mukherjee had not been there? To understand this, we must look back at history, especially the 1930s and 1940s, which were crucial decades for Bengal.

The 1940s: British oppression and natural disasters in Bengal

How did Syama Prasad become the architect of West Bengal? For that, we need to go back to the pre-independence era, particularly the year 1940. At the Lahore session, the Muslim League passed the resolution demanding a separate state for Muslims, formally introducing the Two-Nation Theory. At that time, Syama Prasad was the President of the Hindu Mahasabha in Bengal. Fazlul Haq was the Chief Minister of Bengal, but soon differences emerged between him and Jinnah. Eventually, the Muslim League withdrew its support from Haq’s government.

To prevent the collapse of the cabinet, Syama Prasad stepped in. At that point, undivided Bengal still prioritized the welfare of all its people. But the British had already begun to strategize. In 1942, the Quit India Movement erupted. Several regions in Bengal, particularly Medinipur, joined the armed resistance against British rule. A parallel nationalist government was even formed in Medinipur. In retaliation, British fury was unleashed upon Bengal. Nature too seemed to turn hostile—a devastating cyclone hit Medinipur and the surrounding areas. Amid the disaster and the government’s failure to provide adequate relief, Syama Prasad resigned from the cabinet.

Seizing the moment, Fazlul Haq dismissed the existing cabinet and helped the Muslim League return to power under the leadership of Khwaja Nazimuddin, thus setting the stage for future events.

Hindu Homeland vs. Two-Nation Theory

At that time, Bengal was effectively under Muslim rule. Within a few years, the demand for partition grew stronger. A dark cloud loomed over Bengal’s future. Politically, the question arose: Would Bengal become part of Pakistan? Some voices even advocated for a separate Bengali state. It increasingly appeared inevitable that Bengal would have to be divided from India.

In this scenario, Syama Prasad Mukherjee stepped forward. In 1945, Lord Wavell began consultations with political leaders regarding the partition of India. During this period, Mahatma Gandhi and Muhammad Ali Jinnah held discussions with him. In 1946, Mukherjee participated in talks with the British Cabinet Mission as a representative of the Hindu Mahasabha. He opposed the idea of partition. However, he recognized that India’s division could no longer be stopped.

Determined to ensure that Bengali Hindus could remain part of India, he sought a solution. He insisted that if the country was to be divided, then provinces must also be divided along the same lines — that is, Hindu-majority districts should not be left to Pakistan. To push this demand, he launched a mass movement. A vote was even held regarding Bengal’s partition.

On June 20, 1947, the Bengal Legislative Assembly voted in favor of dividing Bengal. As a result, the new province of West Bengal was created. The Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) considers this a historic moment, asserting that West Bengal was legally formed on that day. Therefore, June 20 is recognized as the birthday of West Bengal, and Syama Prasad Mukherjee is remembered as its founding father.

1930s Bengali…

From the early 1930s to the first few years of the 1950s, Bengal—both undivided and later West Bengal—underwent its most significant political transformations. During these two crucial decades, Syama Prasad Mukherjee emerged as one of the key political figures.

Following the British Commonwealth’s decision in 1932, the Government of India Act of 1935 was adopted, shaping India’s constitutional framework. As a result, Bengal saw its implementation during the subsequent elections. Despite Hindus comprising 45% of Bengal’s population, they were allocated only 80 out of 250 seats in the Legislative Assembly—just 32%. This disproportionate representation sparked widespread protest among Bengali Hindus.

On July 14, 1936, Rabindranath Tagore presided over a massive protest meeting at the Town Hall. Prominent figures like Prafulla Chandra Roy, Sharatchandra Chattopadhyay, Ramananda Chattopadhyay, Sarala Devi, and Neelratan Sircar played leading roles. Despite his poor health, Tagore declared, “After a long time, I have come to a political gathering—not by choice, but because I could not ignore the call of my country’s future.”

In the 1937 elections, the Indian National Congress emerged victorious nationally in the communal vote. However, due to the short-sighted decisions of its leadership, the Muslim League formed the government in Bengal. This outcome deeply troubled Rabindranath Tagore, who was clearly concerned about the deteriorating conditions for Hindus in Bengal.

How to Appease Politics?

In 1935, communal politics presented a supposedly apolitical Rabindranath Tagore at a political gathering. Just as that was forced by circumstance, another situation similarly compelled a prominent Bengali, who came from a non-political background and family, to step into the political arena.

Syama Prasad Mukherjee, though elected to the Bengal Legislative Assembly from the Calcutta University constituency as a Congress or Independent candidate in 1929–30, initially stayed away from active politics. However, during his tenure as Vice-Chancellor of Calcutta University from 1934 to 1938, he became increasingly aware of the growing communal divide encroaching even on university spaces. This changing environment compelled him to engage politically.

In 1937, he was once again elected as an independent member from the Calcutta University seat to the Bengal Legislative Assembly. That same year, he joined the Hindu Mahasabha. In 1938, Calcutta University conferred upon him the honorary D.Litt degree. A year later, in 1939, the Hindu Mahasabha held its annual session in Kolkata under the presidency of Vinayak Damodar Savarkar, where Syama Prasad played a key role. In 1940, he was elected as the Working President of the Hindu Mahasabha. Within a few short years, he emerged as one of the most prominent Bengali political leaders of his time.

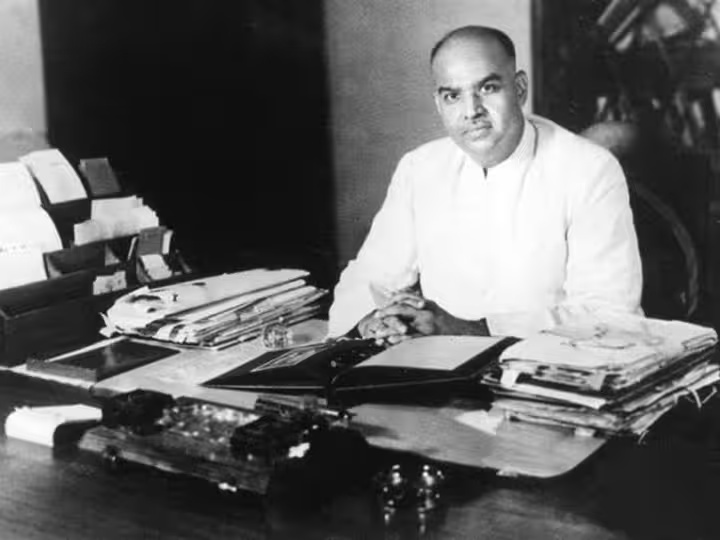

India’s First Industries Minister: Syama Prasad Mukherjee

Syama Prasad Mukherjee was born on July 6, 1901, and lived until 1953—just 52 years. Yet within that short span, he left an indelible mark on Indian politics and intellectual life. As India’s first Minister for Industry, he played a pivotal role in shaping the country’s industrial development. He was the visionary behind the founding of the Indian Institute of Social Welfare and Business Management. The decision to establish the Chittaranjan Locomotive Works was his. He also envisioned the creation of the Bhilai Steel Plant.

After India’s independence, he urged the Hindu Mahasabha to focus on cultural and social activities. However, the political landscape changed rapidly thereafter.

Resignation from Nehru’s Cabinet

In 1950, atrocities against Hindus in East Bengal escalated. Murders, rapes, and the humiliation of Hindu women became daily occurrences. On April 14, 1950, as these events intensified, the Lok Sabha erupted in protest. Dr. Syama Prasad Mukherjee resigned from Prime Minister Nehru’s Cabinet in response to the Nehru-Liaquat Pact—an agreement between Nehru and then Pakistani Prime Minister Liaquat Ali Khan. Mukherjee believed the agreement was made to appease Muslims, which further endangered Bengali Hindus. As a result, the suffering of Hindus in East Pakistan (now Bangladesh) grew unbearable.

Establishment of Jan Sangh

Following his resignation from the Cabinet in 1950, Syama Prasad Mukherjee founded the Bharatiya Jana Sangh the next year, in 1951. After traversing many political developments, this party eventually evolved into the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) in 1980.

To understand the roots of the Jan Sangh, it is essential to examine the political landscape of India at the time. After Mahatma Gandhi’s assassination in 1948, the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) was banned, and its chief, Guruji Golwalkar, was arrested on February 3, 1948. The Congress Party held absolute dominance in national politics. There was no political platform with a nationalist ideology to counter Congress policies, either within or outside Parliament. Social organizations alone were not sufficient to oppose the government’s anti-national decisions. The ban on the RSS further emphasized the need for a political party to represent nationalist voices, thus highlighting the necessity of the Jan Sangh as a political alternative to Congress.

Golwalkar–Syama Prasad Meeting

The idea of forming a political party from within the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) was widely discussed. In 1949, K.R. Malkani, the chief editor of the RSS magazine Organizer, justified the need to establish a political party through his writings. Around that time, many people urged Guruji M.S. Golwalkar, the then RSS leader, to take up a national political role and transform the Sangh into a political party. However, Golwalkar was firm in his belief that the RSS should remain a social organization and not enter politics. In a public statement on November 2, 1948, he made it clear that the RSS had no political agenda or affiliations.

It was during this period that Dr. Syama Prasad Mukherjee met Guruji Golwalkar to discuss the formation of a nationalist political party. In response, Golwalkar agreed to lend support by nominating several RSS pracharaks to assist in the political effort. These included Deendayal Upadhyay, Atal Bihari Vajpayee, Lal Krishna Advani, Jagdish Mathur, Sundar Singh Bhandari, and others.

This marked the beginning of the journey that would eventually lead to the formation of the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), originally known as the Bharatiya Jana Sangh. The Bharatiya Jana Sangh was officially founded on October 21, 1951, at Rajasthan High School in Delhi. Its first president was Dr. Syama Prasad Mukherjee.

Address to The Nation

The movement formally began on October 21, 1951, with a large public gathering. Within just two months of its formation, the Bharatiya Jana Sangh participated in independent India’s first Lok Sabha elections, held in December 1951. During the campaign, the party referred to the nation as ‘Bharat Mata’ and emphasized that the interests of the country should be placed above all else. Their election manifesto promised to strengthen the rural economy, promote agriculture, and encourage an industrial-based economic model. The importance of Swadeshi (economic self-reliance) was also highlighted.

In this first general election, out of a total of 1,111 seats, the Bharatiya Jana Sangh contested 93 and won 3. Two of these seats were from West Bengal: Dr. Syama Prasad Mukherjee from South Kolkata and Durgacharan Banerjee from Medinipur. The third seat was won by Umashankar Trivedi from Chittorgarh, Rajasthan.

Neta Syamaprasad

This is how one can win, lead a party, and take the people forward. Syamaprasad tried to do just that. But he died suddenly during a visit to Kashmir—a death still surrounded by mystery.

If History Took a Turn: Nehru’s Shadow vs. Mukherjee’s Possibilities

After India gained independence in 1947, a major debate emerged: what direction should freedom take? On one side stood Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru, and on the other, Dr. Syamaprasad Mukherjee.

While Nehru became India’s first Prime Minister, Mukherjee became the voice of an alternative India.

Now, decades later, when we revisit that moment in history, one central question arises:

Was Nehru’s path truly the only way forward—or could Mukherjee have offered a more balanced and self-assured India?

Comments